'Show 1, Secret Theatre' review or 'Letting the leash off.'

Show 1, Secret Theatre

Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith, Friday 13th

September 2013

I’m frightened to write this

review. There has been so much debate online about the relative merits of

Secret Theatre – and so much hostility directed towards those who apparently

aren’t embracing the concept enough – that it is becoming very hard to write

about. The enterprise is turning into a theatrical gang war; the new guard

against the old timers. I don’t think it needs to be that way.

The whole idea behind Secret

Theatre is, I think, to question entrenched theatrical assumptions. Sean Holmes

has, bravely, decided to wedge a stick of dynamite underneath a lot of

theatrical norms, particularly within the London theatre scene. Certain expectations

are being blasted away: the text is not King; playfulness can be more important

than profundity; there is no one right way to do theatre. Above all else,

Holmes is responding to an ever-growing group of theatregoers who yearn to

leave the theatre confused, bemused, reeling and fired up, rather than simply

satisfied.

There is no one type of theatre

or theatregoer. There will always be those who go to the theatre to be

reassured or entertained. There will be those who wish to be mystified,

frightened or antagonised – and there will be others who just want to dance and

sing. There will also be those determined to hate theatre, no matter what. One

cannot hope to make theatre which satisfies all these audiences – but I do

think we should be aiming towards creating a public, critical and institutional

atmosphere that embraces all of these potential theatregoers, even the theatre

haters.

What concerns me about the debate

surrounding Secret Theatre right now is how exclusive and unforgiving it is

becoming. There is the sense that one side is right and everyone else is wrong.

I’m not saying this is what Sean Holmes or they Lyric are pushing for; I’m

certain it isn’t. But it frustrates me that, in waving the flag for a new,

unfettered and open-ended type of the theatre, many of its greatest fans are beginning

to sound narrow-minded. There is no right or wrong in theatre.

Perhaps the unequivocal attitude

taken by so many is only in response to a similar approach adopted by critics

and practitioners on ‘the other side’, who have proved equally stubborn about

their own theatrical code, i.e. the text should be on the stage and, if it isn’t

there, the show is a lost cause. Still, it seems silly for the ‘new wave’

theatre bods to falls into the same traps all over again.

I’m hoping this is all just an

early stage in the process; a particularly violent push towards a new and wider

theatrical landscape. It is interesting that all of this turbulence is happening

at a time when the position of critics is particularly precarious. All the Indy

lot have gone and now Libby Purves is out too. Michael Billington is angry. All

of this is playing (exhilarating) havoc with the theatrical climate.

Despite all this, what has struck

me about Secret Theatre so far, aside from the debate, is just how liberated

the actors seem – and how completely at ease they are with expressing themselves

in whatever way they see fit. Both the plays re-invented in Show 1 and 2 (and I

will be mentioning the Show Titles in a bit, only because I think it adds to

the discussion and how on earth can that be a bad thing?) are peppered with

odd, seemingly incongruous but deeply effective, even private moments from the

actors. The songs, in particular, feel at odds with the text but brilliantly in

tune with the production. Leo Bill wails out a number during Show 1 that splits

the soul in two. It is the sound of a person breaking in half and it is how

Woyzeck’s soul would sound, were it turned into song.

There are other moments, too,

which feel out of place but grab one’s attention with such force. In Show 2, a slight

moment that sticks in the head. Stella sticks a tiny photo of Stan on a massive

blank wall. The hold that Stan takes on Stella’s soul – the disproportionate

control he has on a world beyond his reach or even comprehension - blasts out

in that moment. Later, Stella fizzes a

can of coke in Blanches’s face. Blanches refuses to react. This is a woman who has

somehow learnt to ignore the physical; to create a deeply private and untouchable

landscape that cannot be touched by reality, no matter how close it gets.

There are countless improvised

sparks that light up both shows and suggest an extraordinarily free yet probing

rehearsal process. In Show 1, there is a montage that must have been earned

through such intelligent work. The cast sit facing the audience, their glasses

raised for an empty toast. They sing an anthem we cannot understand but that

feels commanding, cruel and unforgiving. Everything feels assured but out of

kilter, too. A man slides forward in a slip of a dress, defiant and desperate.

The whole production has the strangest air of taking place elsewhere; as if the

cast is performing to an audience just a few metres to the left of us. As an

audience, we feel examined yet ignored.

There is something deliciously

unknowable about Show 1 – and so many elements that feel provocatively and

usefully out of reach. Not one song is ever finished. No speech hits an end

note. Breakdowns never break down. Love stories never flair up. There isn’t a

hug that works or a punch that makes one flinch. And there is a central

character that runs around and around the stage, yet never makes it anywhere.

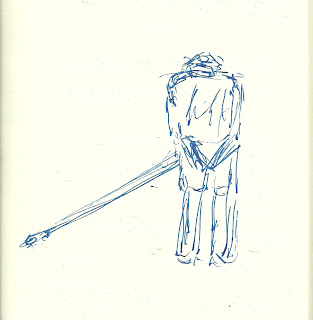

Near the close of Show 1, Woyzeck

– who has temporarily released himself – ties himself back to a leash on stage.

He instinctively returns to his set positions. Questions come tumbling off the

stage. How many limits do we need to make sense of a show, to make sense of our

lives? What of the physical and theoretical limits of the stage? Do we let the stage

rule us – or do we take off the leash and see just how far we can run?

Comments

Post a Comment